You are probably wondering why I have decided to write about the number 27.

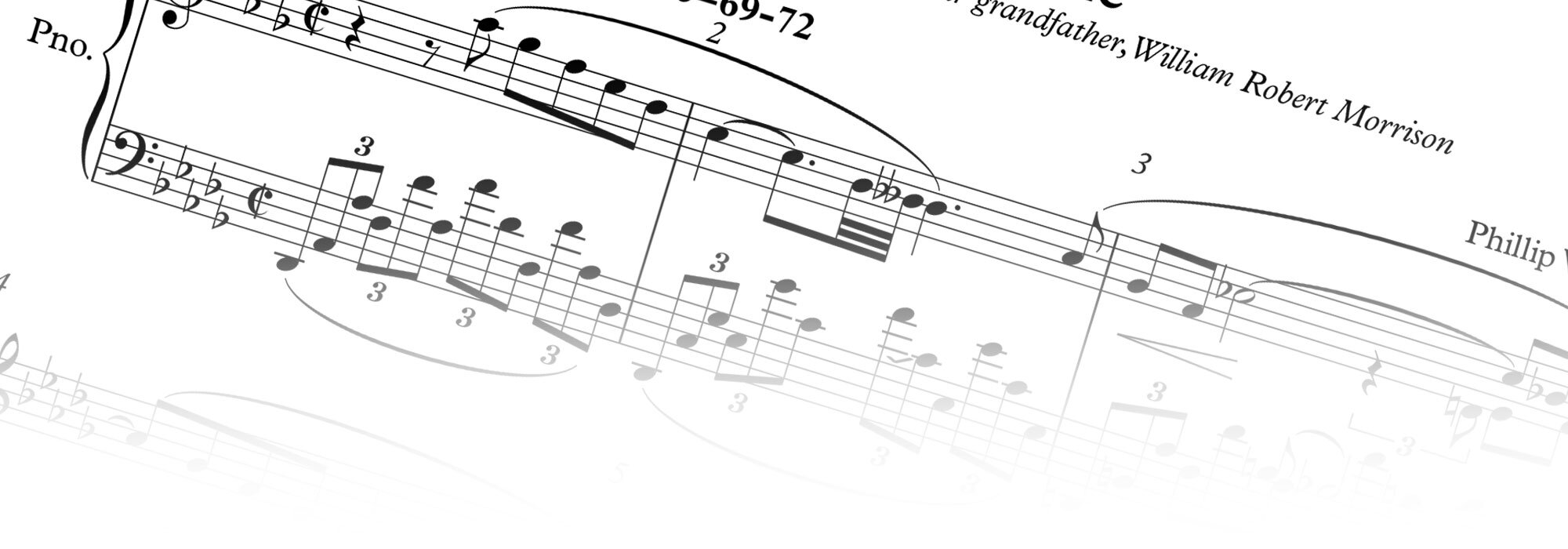

Well, 27 years ago, at the nearly forgotten age of 14, the Sydney based publishing house of J. Albert and Sons Pty Ltd, published my very first composition for piano solo, titled Daybreak. Franz Holford was the editor of Albert’s Classical/Educational Division and was steadfastly dedicated to nurturing the strengths and talents of Australian composers.

Now, 27 years later, and 6 years after the sad tidings of his death reached me via radio to change the weight of my world, the Centre for Studies in Australian Music at the University of Melbourne is set to publish a book written by Franz in 1992, titled Middle See, as a much deserved and sadly belated tribute to his vast, unordinary life and work.

Born in Heidelberg, Germany, 27 is also the sum total of those numbers which comprise the date of his birth – 9.11.1906 .

Music when soft voices die,

Vibrates in the memory

Here are some of those vibrations:

To enter Hunters Hill was to enter another world, and to enter my teacher’s house on Woolwich was to walk into a world within another world. 27 was an old stone house secluded by a high stone fence on which had grown a rambling hedge. After unbolting a heavy wooden gate you would approach the house from a gently curving cobbled path, flanked either side by leaf-shadowed lawns, gingko and cherry trees. Actually, the two cherry trees in my family’s backyard are from Franz, and once a year they dapple the small wood-chip piles with their lolly-pink clusters of a most vibrant hue, and then, cherries!

Here are some lines from a poem by Franz:

Day’s beckoning touched the shimmering sky And was up at the trees on the hill,

When two eager hearts were ready to fly west To the land of ripe berries Where dreams come true and plum-red cherries grew.

27’s verandah, once rickety and uneven, was admirably rebuilt, ironwork and all, by my father, I suppose as an exchange for the lessons I was receiving.

Above the entrance, a small lead-light window featuring two noisy miners.

I would knock the opening bars of Fifth symphony – da da da daa – and

Franz would whistle the answering sequence in response – da da da daa – as he made his way unseen from his study to appear at the far end of the corridor to greet my parents and me, usually wearing a grey suit and tie, pipe in hand.

Arts Consultant, James Murdoch once described him as a large man of imposing stature, forthright, even eccentric and as one who produced in most people a remarkable affection. He mostly spoke with what might be considered an English accent, somewhat “well –to-do”, but more precisely, he simply appeared well spoken. When relaxed or a little tired, or even a little sad, he would gently slip into a German accent, world-weary, or at times, whimsical.

Welcome he would say, half bowing to usher us in. I would go first, somewhat nervously so to greet him, and my parents, equally in awe, would follow. The corridor with walls pasted in the finest regency stripe wall-paper almost divided the house and was stately laid with a hall-runner which led to what I came to always call the room with the silver in it; a room paved in large black and white linoleum floor tiles and furnished with heavy pieces of mahogany furniture, in the centre of which stood a table on which were placed mirror-clean pieces of silver – lots of it! From that room I have a small silver cigarette case which Franz gave me, on the lid of which is reproduced Rembrandt’s painting The Night Watch. Before this, on immediately entering the house, and to your left, was Franz’s bedroom, about which I was a little more than curious, only because I could never imagine him sleeping – not even the four hours he claimed he only needed to sustain him. To the right, and directly opposite this room was a small, magical sitting room – beautiful, isn’t it! – he would say – which no one ever seemed to sit in and about which I had a feeling no one even entered, Midway down the corridor, and to the right, was a small claustrophobic passageway which lead to the library proper. This was a dark and grand affair – walls lined with shelves full of beautifully bound volumes. Books on Bach, Beethoven and Berlioz, some of which are now in my own collection, as well as books of a more literary nature : books on Ottoline Morrell, and the newly released editions of letters and diaries of Virginia Woolf, published by The Hogarth Press, their dust jackets removed. There were signed and limited editions of poetry – again, some of which are now in my own collection. If I hold them close and breathe in deeply, a faint smell of 27 is still there, and an abounding past mingles with the uninhabited present:

Odours, when sweet violets sicken,

live within the sense they quicken.

In the far left hand corner of the library stood an elegantly crafted Edwardian desk, four drawers – two either side – with a green thick textured fabric top, on which were placed large prints of birds – lapwings and the like – an a beautiful brass inkwell. It is at that very same desk I am now writing this article.

But if by chance you turned left before entering the library proper, you would find yourself at the entrance way to the tiniest of rooms : Franz’s workroom. It was small, very small , and seemed to me to be the one room I which he lived most, and where on occasion, a small , very small skylight above his paper-strewn desk gave 27’s resident possum a peek into his rainbowy world. It was in this room he did whatever after-hours work had to be done on any forthcoming Albert Edition publications, attended his correspondence, and listened to static broadcasts through a small radio. Framed portraits, inscribed to Franz personally from such musical heavy-weights as Sir John and Lady Evelyn Barbirolli and Felix Weingartner covered the walls. There was even a signed silhouette of de Pachmann dated Londres 1922 – all of which are now in my possession and take pride of place as permanent treasures in my music room. But reigning supreme, and defying all, the dank and dusty death mask of Beethoven. Stacked on shelves, albeit willy-nilly, were the Albert publications of Franz’s own works, mostly his songs, in green covers. Caterpillars he’d call them! However, if you were to actually pass this worldly workroom, you’d find yourself again in the room with the silver in it , where the two entrances also served as two exits, depending on whether you were coming or going. Turning right- well – you would find yourself in the kitchen. Like the sitting room in which no one ever sat, and I suppose too, a little like the bedroom I couldn’t imagine Franz sleeping in, the kitchen seemed a cooking place in which no one ever cooked. I remember it being very German, a little too dark perhaps, somewhat spacious, and of the colour green – the same green as the covers of his music – caterpillar green! Once however, he did whip up an asparagus omelette for me which tasted better than it looked. It too was green! Turning around, if you looked across the way, beyond the room with the silver in it, you would see Franz’s piano, a brown baby Bluthner grand, which not surprisingly he called Baby, its ivory keys lovingly yellowed with age. For want of a better name, Baby’s room was, I suppose, the music room, which had the quaint defect of a ceiling in need of repair, and was the only other room, aside from the small – very small – study where his caterpillars were, in which I saw him. It was also the room in which I received my lessons every Sunday afternoon. In this room I learnt how not to play the opening measures of Bach’s Prelude No. 5 in D major from the “48” and how to line with silver the floating clouds of Chopin’s Nocturne in Eb opus 9 No.2. That took some doing! At one time, when it simply wasn’t working in the simple way it should, we took a stroll through his garden of maiden-hair ferns:

Can you see the Nocturne? he asked.

In this room I also learnt to pound my way through the relentlessly dotted rhythm of a Passacaglia by Bax, and to hiss like a cat in the Andaluza by Granados.

Franz wasn’t fond of cats – not at all! – yet, somehow they figured now and then in his teaching – strange as that may seem. In a note sent to me at the time he was teaching me to play Rachmaninov’s famous Prelude in C# minor, he wrote:

Do keep up the work on the Rachmaninov triplets – they are extremely effective if well played, but if not, they sound like a cat in a crockery cupboard.

It was alos in this room he once said to me after a bad performance: Don’t come to me with egg on your tie! Eggs again – and at that, I turned green!. There too I used to watch him float one smoke ring through the centre of another while puffing on his pipe. Clever trick!

With Baby were two chairs and a lounge – 3 seater I think – a carved sideboard on which sat a silver tray and a decanter of Dimples, a fire place and mantle, over which hung a heavy tapestry, and on the floor, to either side sat a brass bucket he delighted in telling you was made from brass off Bismarck’s ship, and several stokers. Two ornately patterned plates in filigreed colours of orange, white, black and gold balanced precariously at either end of the mantle. The only reproductions hanging on the walls of this room which come to mind were Constable’s Salisbury Cathedral and a painting by Cezanne, whose work both Franz and I adored. Constable’s clouds were perhaps a little too English but silver-edged enough to aid me visually in producing the sound Franz required of me in playing the Nocturne, though the texture was really more like that of the Cezanne. Next to Baby stood a small table on which Franz would place whatever flowers he had for my mother, and a book for me. Usually, one or two camellias, pink or white, or both, with a piece of maiden-hair fern around which he gently folded a tissue. My favourite flowers of all, which are still my favourite to this day, were the gardenias : small blooms like antique white porcelain, resting on polished green leaves – caterpillar green! – that coated the air thick with a fragrance both sweet and sad. For some reason, I always associate gardenias with Chopin’s Preludes and the rain.

I remember another room, which on leaving 27 was to the right off the hallway, just before you came to Franz’s bedroom. I once caught a glimpse inside to see stacks upon stacks of old 78 rpm recordings – some of his own, and what I think was an old square piano.

In the late seventies, for reasons unknown to me, Franz left 27, never to return. It was a home in which all who knew him, thought he might die – sadly this was not to be.

Apart from those books I now have which once were his and lend a certain charm and nobility to my own library, and aside from the desk and signed photos, I also have a chair, beautifully carved and covered in a fine and fragile tapestry, faded but true. Now I think about it, it probably came from the sitting room in which no one ever sat. No one sits in it now.

Rose leaves when the rose is dead,

are heaped for the beloved’s bed.

How to finish? I have written elsewhere that not a day goes by when I do not think of him, or beckon his spirit to guide me in all things I do. This is true! Six years after his passing he influences and intrigues me no less than the day I first met him in his cedar-paneled office at the publishing house of J. Albert & Sons. Pty Ltd, those 27 years ago. Six years after his passing, the sense of him remains ever keen – if not more keen – but with the added tinge that is nostalgia.

James Murdoch wrote of Franz and his work at the time of his passing: